A glyph (/ɡlɪf/ GLIF) is any kind of purposeful mark. In typography, a glyph is "the specific shape, design, or representation of a character".[1] It is a particular graphical representation, in a particular typeface (or computer font), of an element of written language. (That 'element' is called a grapheme – the conceptual abstraction of some letter, number or symbol, which is independent of the glyph designed to represent it in a particular font.)

Glyphs, graphemes and characters

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2021) |

In modern English, each symbol (such as a letter or numerical digit) is a grapheme that can be represented by a single glyph that is unique to the font where it used. Detailed differences in the design of each glyph in the repertoire is the distinguishing feature of a typeface (or computer font) but in each case the grapheme being represented is constant.

In most languages written in any variety of the Latin alphabet except English,[a] the use of diacritics to signify a sound mutation is common. For example, the grapheme ⟨à⟩ requires two glyphs: the basic |a| and the grave accent |`|. In general, a diacritic is regarded as a glyph,[2] even if it is contiguous with the rest of the character like a cedilla in French, Catalan or Portuguese, the ogonek in several languages, or the stroke on a Polish ⟨Ł⟩. Although these marks originally had no independent meaning, they have since acquired meaning in the field of mathematics and computing, for instance.

Conversely, in the languages of Western Europe, the dot (formally, tittle) on a lower-case ⟨i⟩ is not a glyph in itself because it does not convey any distinction, and an |ı| in which the dot has been accidentally omitted is still likely to be recognized correctly. However, in Turkish and adjacent languages, this dot is a glyph because that language has two distinct versions of the letter i, with and without a dot.

In Japanese syllabaries, some of the characters are made up of more than one separate mark, but in general these separate marks are not glyphs because they have no meaning by themselves. However, in some cases, additional marks fulfil the role of diacritics, to differentiate distinct characters. Such additional marks constitute glyphs.

Some characters such as |æ| in Icelandic and |ß| in German may be regarded as glyphs. They were originally typographic ligatures, but over time have become characters in their own right; these languages treat them as unique letters. However, a ligature such as |fi|, that is treated in some typefaces as a single unit, is arguably not a glyph as this is just a design choice of that typeface, essentially an allographic feature, and includes more than one grapheme.[2] In normal handwriting, even long words are often written "joined up", without the pen leaving the paper, and the form of each written letter will often vary depending on which letters precede and follow it, but that does not make the whole word into a single glyph.

Older models of typewriters required the use of multiple glyphs to depict a single character, as an overstruck apostrophe and full stop to create an exclamation mark. If there is more than one allograph of a unit of writing, and the choice between them depends on context or on the preference of the author, they now have to be treated as separate glyphs, because mechanical arrangements have to be available to differentiate between them and to print whichever of them is required.

In computing as well as typography, the term character refers to a grapheme or grapheme-like unit of text, as found in writing systems (scripts). In typography and computing, the range of graphemes is broader than in a written language in other ways too: a typeface often has to cope with a range of different languages each of which contribute their own graphemes, and it may also be required to print non-linguistic symbols such as dingbats. The range of glyphs required increases correspondingly. In summary, in typography and computing, a glyph is a graphical unit.[2]

Representative glyph

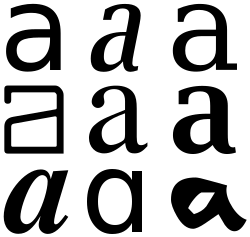

[edit]In material about a grapheme, the author must select one of the range of glyphs that could be used for it, without intending to convey any implication that it is the "correct" one. This choice is called a representative glyph.[3]

See also

[edit]- Character encoding – Using numbers to represent text characters

- Complex text layout – Neighbour-dependent grapheme positioning

- Glyph Bitmap Distribution Format – File format for storing bitmap fonts

- Hieroglyph – Ancient Egyptian writing system

- International Phonetic Alphabet § Brackets and transcription delimiters

- Letter cutting – Form of inscriptional architectural lettering

- Palaeography – Study of handwriting and manuscripts

- Punchcutting – Craft used in traditional typography

- Sort (typesetting) – Block with a typographic character etched on it, which is lined up with others to print text

Notes

[edit]- ^ ignoring special cases such as personal names and imported words

References

[edit]- ^ Strizver, Ilene. "Confusing (and Frequently Misused) Type Terminology, Part 1". fonts.com. Monotype Imaging. Archived from the original on 25 December 2011.

- ^ a b c Whistler, Ken; Davis, Mark; Freytag, Asmus (11 November 2008). "Characters Vs Glyphs". Unicode Consortium.

- ^ "Chapter 24: About the Code Charts". Unicode® 17.0.0. Unicode Consortium. September 2025.

A representative glyph is not a prescriptive form of the character, but rather one that enables recognition of the intended character to a knowledgeable user and facilitates lookup of the character in the code charts. In many cases, there are more or less well-established alternative glyphic representations for the same character.