You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in German. (November 2014) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

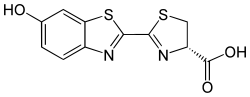

(color coding: black=carbon, white=hydrogen, blue=nitrogen, red=oxygen, yellow=sulfur)

Luciferin (from Latin lucifer 'light-bearer') is a generic term for the light-emitting compound found in organisms that generate bioluminescence. Luciferins typically undergo an enzyme-catalyzed reaction with molecular oxygen. The resulting transformation, which usually involves breaking off a molecular fragment, produces an excited state intermediate that emits light upon decaying to its ground state. The term may refer to molecules that are substrates for both luciferases and photoproteins.[1] Luciferins and luciferases are usually specific to particular species or taxonomic groups.

History

[edit]As early as the 17th century, Robert Boyle discovered through experimentation that every bioluminescent system requires oxygen.

In the early 18th century, René Réaumur noted that powder made from dried and ground bioluminescent creatures glowed when water was added. The first experimental studies of luciferin–luciferase systems were performed by the French scientist Raphael Dubois. Utilizing glow-worms and fireflies in 1885, he discovered that a substance is consumed during the light-producing reaction. Dubois eventually extracted two compounds responsible for the glow; the first component, resistant to heat, was named luciferin. He called the separate heat-labile component luciferase. Today it is known that luciferase is the enzyme that acts on its matching luciferin substrate. By mixing luciferin with luciferase in the presence of oxygen, Dubois was able to reproduce natural bioluminescence.[2]

Investigations continued through the work of Edmund Newton Harvey in the early 20th century.[3] He demonstrated that luciferin–luciferase systems are taxon specific: a luciferin from one species is not turned over by the luciferase of another. Major advances in uncovering the structure followed from the 1950s through the work of Nobel laureate Osamu Shimomura.

Properties

[edit]The molecule bound to the luciferase active site producing the light is what scientists define as luciferin. While many different types of luciferin molecules exist requiring divergent reaction mechanisms, general principles can be extracted from common conversions. Luciferase catalyzes this reaction using oxygen alongside certain cofactors like ATP or Mg²⁺. The oxidized luciferin then enters a transition state (I). After decarboxylation, luciferin reaches an excited state (P*). It then relaxes to its ground state (P) after a few nanoseconds and emits a photon. Since it can also be excited by irradiation with light, a luciferin product following decarboxylation can also be considered a fluorophore.

Principles

[edit]Reaching the excited state (P*) requires lots of energy. For a luciferin molecule to emit a green photon with a wavelength of 500 nm, it calls for about 250 kJ/mol; in comparison, the hydrolysis of ATP to ADP and phosphate releases about 30 kJ/mol. On top of that, the energy has to be liberated in a single step. This energy is supplied by molecular oxygen when its weak double bond is broken and a stronger bond is formed: for example CO₂ which is about 300 kJ/mol more stable.[4]

The most common mechanism is the formation of a four-membered ring, a dioxetane or dioxetanone. After decarboxylation, luciferin is energized to its excited state.

Sometimes observed chemiluminescence differs from expectation. This is due to the fact that enzyme-bound luciferins oxidize to emit differently than free luciferins excited by light. Another reason for this phenomenon is that through resonance, excitation energy is transferred to a second molecule, as in Aequorin transferring to GFP in Aequorea victoria.[5]

Quantum yield

[edit]The efficiency of the conversion of a luciferin by its luciferase is determined by the quantum yield. The quantum yield is the number of emitted photons per converted luciferin molecule.[6] A quantum yield of 1 would mean that one photon is released for every converted luciferin molecule. The highest quantum yield Q to date has been demonstrated for firefly luciferin from Photinus pyralis with Q = 0.41. This is a statistical average observed across the system of excited luciferin molecules: if 100 molecules of firefly luciferin were excited, an average of 41 photons would be emitted.

Types

[edit]Bioluminescent systems are not evolutionarily conserved. Luciferins share no obvious sequence homology. Because of the chemical diversity of luciferins, there is no clear unifying mechanism of action, except that all require molecular oxygen.[7] Despite this, luciferins occur across 17 different phyla and at least ~700 genera.[8] It seems they were often “invented” evolutionarily; phylogenetic studies show that luciferin-luciferase systems have over 30 independent origins.[9] Emitted colors range from blue to red (400–700 nm), with blue hues most common and red emissions rare.[10] This makes sense considering the majority of bioluminescent organisms live in the ocean where blue light penetrates water most effectively. It is not known just how many types of luciferins there are, but some of the better-studied compounds are listed below.

Firefly

[edit]

Firefly luciferin is the luciferin found in many Lampyridae species, such as P. pyralis. It is the substrate of beetle luciferases (EC 1.13.12.7) responsible for the characteristic yellow light emission from fireflies, though can cross-react to produce light with related enzymes from non-luminous species.[11] The chemistry is unusual, as adenosine triphosphate (ATP) is required for light emission, in addition to molecular oxygen.[12]

Snail

[edit]

Latia luciferin is, in terms of chemistry, (E)-2-methyl-4-(2,6,6-trimethyl-1-cyclohex-1-yl)-1-buten-1-yl formate and is from the freshwater snail Latia neritoides.[13]

Bacterial

[edit]

Bacterial luciferin is two-component system consisting of flavin mononucleotide and a fatty aldehyde found in bioluminescent bacteria.[14]

Coelenterazine

[edit]

Coelenterazine is found in radiolarians, ctenophores, cnidarians, squid, brittle stars, copepods, chaetognaths, fish, and shrimp. It is the prosthetic group in the protein aequorin responsible for the blue light emission.[15]

Dinoflagellate

[edit]

Dinoflagellate luciferin is a chlorophyll derivative (i. e. a tetrapyrrole) and is found in some dinoflagellates, which are often responsible for the phenomenon of nighttime glowing waves (historically this was called phosphorescence, but is a misleading term). A very similar type of luciferin is found in some types of euphausiid shrimp.[16]

Vargulin

[edit]

Vargulin is found in certain ostracods and deep-sea fish, to be specific, Poricthys. Like the compound coelenterazine, it is an imidazopyrazinone and emits primarily blue light in the animals.

Fungi

[edit]

Foxfire is the bioluminescence created by some species of fungi present in decaying wood. While there may be multiple different luciferins within the kingdom of fungi, 3-hydroxy hispidin was determined to be the luciferin in the fruiting bodies of several species of fungi, including Neonothopanus nambi, Omphalotus olearius, Omphalotus nidiformis, and Panellus stipticus.[17]

Usage in science

[edit]Luciferin is widely used in science and medicine as a method of in vivo imaging, using living organisms to non-invasively detect images and in molecular imaging. The reaction between luciferin substrate paired with the receptor enzyme luciferase produces a catalytic reaction, generating bioluminescence.[18] This reaction and the luminescence produced is useful for imaging—examples include detecting cancerous tumors, or measuring gene expression.

References

[edit]- ^ Hastings JW (1996). "Chemistries and colors of bioluminescent reactions: a review". Gene. 173 (1 Spec No): 5–11. doi:10.1016/0378-1119(95)00676-1. PMID 8707056.

- ^ Haddock, S. H. D., Moline, M. A., & Case, J. F. (2010). “Bioluminescence in the sea.” Annual Review of Marine Science, 2, 443–493. doi:10.1146/annurev-marine-120308-081028

- ^ E. N. Harvey: Bioluminescence. Academic, New York 1952.

- ^ Schmidt-Rohr, Klaus (2020-02-11). "Oxygen Is the High-Energy Molecule Powering Complex Multicellular Life: Fundamental Corrections to Traditional Bioenergetics". ACS Omega. 5 (5): 2221–2233. doi:10.1021/acsomega.9b03352. PMC 7016920. PMID 32064383.

- ^ Kendall, Jonathan M; Badminton, Michael N (1998-12-01). "Aequorea victoria bioluminescence moves into an exciting new era". Trends in Biotechnology. 16 (5): 216–224. doi:10.1016/S0167-7799(98)01184-6. ISSN 0167-7799.

- ^ Emil H. White, Eliezer Rapaport, Howard H. Seliger, Thomas A. Hopkins: The chemi- and bioluminescence of firefly luciferin: an efficient chemical production of electronically excited states. In: Bioorg. Chem., vol. 1, nos. 1–2, September 1971, pp. 92–122, doi:10.1016/0045-2068(71)90009-5.

- ^ Hastings JW (1983). "Biological diversity, chemical mechanisms, and the evolutionary origins of bioluminescent systems". Journal of Molecular Evolution. 19 (5): 309–321. Bibcode:1983JMolE..19..309H. doi:10.1007/BF02101634. PMID 6358519. S2CID 875590.

- ^ J. W. Hastings: Bioluminescence. In: N. Sperelakis (ed.): Cell Physiology, 3rd ed., Academic Press, New York 2001, pp. 1115–1131.

- ^ P. J. Herring: Systematic distribution of bioluminescence in living organisms. In: J Biolumin Chemilumin., 1(3), 1987, pp. 147–163, PMID 3503524.

- ^ Brodl, Eveline; Winkler, Andreas; Macheroux, Peter (2018-01-01). "Molecular Mechanisms of Bacterial Bioluminescence". Computational and Structural Biotechnology Journal. 16: 551–564. doi:10.1016/j.csbj.2018.11.003. ISSN 2001-0370. PMC 6279958.

- ^ Viviani VR, Bechara EJ (1996). "Larval Tenebrio molitor (Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae) Fat Body Extracts Catalyze Firefly D-Luciferin-and ATP-Dependent Chemiluminescence: A Luciferase-like Enzyme". Photochemistry and Photobiology. 63 (6): 713–718. doi:10.1111/j.1751-1097.1996.tb09620.x. S2CID 83498776.

- ^ Green A, Mcelroy WD (October 1956). "Function of adenosine triphosphate in the activation of luciferin". Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 64 (2): 257–271. doi:10.1016/0003-9861(56)90268-5. PMID 13363432.

- ^ EC 1.14.99.21. ORENZA: a database of ORphan ENZyme Activities, accessed 27 November 2009.

- ^ Madden D, Lidesten BM (2001). "Bacterial illumination" (PDF). Bioscience Explained. 1 (1).

- ^ Shimomura O, Johnson FH (April 1975). "Chemical nature of bioluminescence systems in coelenterates". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 72 (4): 1546–1549. Bibcode:1975PNAS...72.1546S. doi:10.1073/pnas.72.4.1546. PMC 432574. PMID 236561.

- ^ Dunlap JC, Hastings JW, Shimomura O (March 1980). "Crossreactivity between the light-emitting systems of distantly related organisms: Novel type of light-emitting compound". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 77 (3): 1394–1397. Bibcode:1980PNAS...77.1394D. doi:10.1073/pnas.77.3.1394. PMC 348501. PMID 16592787.

- ^ Purtov KV, Petushkov VN, Baranov MS, Mineev KS, Rodionova NS, Kaskova ZM, et al. (July 2015). "The Chemical Basis of Fungal Bioluminescence". Angewandte Chemie. 54 (28): 8124–8128. Bibcode:2015ACIE...54.8124P. doi:10.1002/anie.201501779. PMID 26094784.

- ^ Badr CE, Tannous BA (December 2011). "Bioluminescence imaging: progress and applications". Trends in Biotechnology. 29 (12): 624–633. doi:10.1016/j.tibtech.2011.06.010. PMC 4314955. PMID 21788092.

External links

[edit]- "Major luciferin types". The Bioluminescence Web Page. University of California, Santa Barbara. 2009-01-09. Retrieved 2009-03-06.