| aka: Dharawal, Darawal, Turawal, Thurawal, Turuwul, Five Islands tribe, Cowpastures tribe, Shoalhaven tribe, Tharawal (AIATSIS), nd (SIL)[1] | |

Sydney Basin bioregion | |

| Hierarchy | |

|---|---|

| Language family: | Pama–Nyungan |

| Language branch: | Yuin–Kuric |

| Language group: | Yora |

| Group dialects: | Tharawal[2] |

| Area | |

| Bioregion: | Sydney Basin |

| Location: | Sydney and Illawarra, New South Wales |

| Coordinates: | 34°S 151°E / 34°S 151°E |

| Rivers | Georges and Shoalhaven |

| Notable individuals | |

| Bundel Gogy Bill Worrall Wagin Yugur Arawarra Rosie Russell Jack Carpenter Captain Brooks (Munnag) Tullimbah Biyarung (Biddy Giles) Joe Anderson Broughton (Toodwik) Broger Johnny Crook (Yunbai) John Pigeon (Warroba) Stewart (Nillang) Emma Timbery | |

Dharawal is a term referring to the groups of Aboriginal Australian people who shared the Dharawal language.[2] Traditionally, they lived in defined hunter–fisher–gatherer family groups or clans with ties of kinship, along the coastal area through what is now the Campbelltown, Wollongong, Port Kembla, Sutherland Shire and Nowra regions of New South Wales.

Etymology and alternative names

[edit]Dharawal means cabbage palm.[3] Alternative spelling and pronunciation of this term include: Tharawal, Darawad, Thurawal, Turrubul, Turuwal and Turuwul.[4]

Language

[edit]The Dharawal people spoke the Dharawal language, which was quite similar to the neighbouring coastal languages of Dharug, Dhurga, Thawa, Awabakal and Dyirringany. These languages are sometimes grouped together as dialects under the broader title of either Yuin or Katungal language, various forms of which are believed to have been spoken along most of the southern and central coastlines of New South Wales.[5]

The language of the Gandangara people in the mountains inland from Dharawal country was also closely associated with Dharawal, and these two groups shared some cultural ties.[5] The Gandangara appear to have known the Dharawal language as Gur Gur.[6]

Country

[edit]According to ethnologist Norman Tindale, traditional Dharawal lands encompass some 450 square miles (1,200 km2) from the southern shore of Botany Bay, along the Georges River to Campbelltown and then south through Port Hacking, Wollongong to the Shoalhaven River and the Beecroft Peninsula.[4]

Clans

[edit]The Gweagal clan of the area now referred to as the Sutherland Shire were also known as the "Fire Clan". They were first Aboriginal Australian people to make meaningful contact with Captain Cook.

The Cubbitch Barta or Cobbitty Barta (meaning place of white pipe clay)[6] clan were located in the Narellan and Campbelltown region of what is now the outer south-western suburbs of Sydney. They were also known by the early British colonists as the "Cowpastures tribe" as this was the area where the lost cattle from the First Fleet were rediscovered. A registered Indigenous land use agreement was made by modern representatives of the clan for Helensburgh in 2011.[7]

The country of the Wadi Wadi clan (also known to the colonists as the "Five Islands tribe" referring to the Five Islands just off the coast of Port Kembla) includes the Illawarra, Wollongong and Port Kembla areas. The Dharawal name for the Five Islands is Woolyungah, which is now incorporated into the name of the adjacent city of Wollongong.[8]

Around the Shoalhaven River region and northern part of Jervis Bay, the various clans such as the Numbaa, Meroo, Jerringong and Worrigee were known to the colonists collectively as the "Shoalhaven tribe". The descendants of these people are now referred to as the Jerrinja.[9][10]

There is some debate as to the southern extent of the Dharawal speaking people and where those who spoke the Dhurga language (which is quite similar to Dharawal) began. At the time of British colonisation this was a border region between the two groups and it is possible Dharawal was spoken as far south as Ulladulla.[10]

Lifestyle and culture

[edit]The Dharawal people lived mainly off the produce of local plants, fruits and vegetables, as well as by hunting marsupials such as kangaroo and possum, and also by fishing and gathering shellfish products. The women collected vegetable foods and were well known for their fishing and canoeing prowess. There are a large number of shell middens still visible in Dharawal country and a glimpse of the Dharawal lifestyle can be drawn from the analysis of the midden sites. Their main source of carbohydrate came from collecting and treating the seeds and roots of the burrawang plant, and then grinding and cooking the resultant flour into flat bread-like cakes.[8]

The Dharawal had various totems but sea mammals such as dolphins, porpoises and whales had special status amongst these people.[11] The historical artwork (rock engravings) of the Dharawal people is visible on the sandstone surfaces throughout their language area and charcoal and ochre paintings, drawings and hand stencils can be found on rock surfaces and in rock shelters and overhangs.[5]

For example, there is a public viewing site of one group of engravings at Jibbon Point, showing a whale and a wallaby. According to an early Dharawal informant, Biddy Giles,[b] these images commemorated notable events, a successful hunt and the stranding of a whale.[13][14]

History

[edit]Pre-colonial

[edit]Archaeological evidence has shown that the Dharawal and their ancestors have lived in the area for at least 8,200 years, with human habitation of this region and the associated (now submerged) continental shelf probably predating this by an additional 20,000 to 30,000 years.[5]

British invasion

[edit]

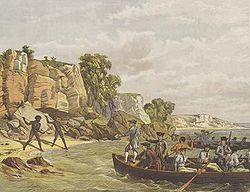

Dharawal life was changed dramatically by the arrival of the British explorer, Captain James Cook, in 1770. Cook made his first landing upon the eastern coast of Australia on Gweagal country on the southern side of Botany Bay. The artist Sydney Parkinson, one of HMS Endeavour's crew members, wrote in his journal that the Indigenous people threatened them shouting words he transcribed as warra warra wai, which he glossed to signify 'Go away'. According to spokesmen for the contemporary Dharawal community, the meaning was rather 'You are all dead', since warra is a root in the Dharawal language meaning 'wither', 'white' or 'dead'. As Cook's ship hove to near the foreshore, it appeared to the Dharawal to be a white low-lying cloud, and its crew 'dead' people whom they warned off from returning to the country.[15]

Cook himself wrote:

"as we approached the Shore they [the Aboriginal people] all made off, except two Men, who seem'd resolved to oppose our landing...for as soon as we put the boat in they again came to oppose us, upon which I fired a musket between the two, which had no other effect than to make them retire back, where bundles of their darts lay, and one of them took up a stone and threw at us, which caused my firing a second musket, load with small shot; and altho' some of the shot struck the man, yet it had no other effect than making him lay hold on a target. Immediately after this we landed, which we had no sooner done than they throw'd two darts at us; this obliged me to fire a third shot, soon after which they both made off, but not in such haste but what we might have taken one."[16]

He went on to say that:

"in the afternoon 16 or 18 of them came boldly up to within 100 yards of our people at the watering place...all they seem'd to want was for us to be gone. After staying a Short time they went away. They were all Arm'd with Darts and wooden Swords."[16]

Early colonial

[edit]From 1788, when permanent British colonisation of their homelands began, the Dharawal people proved to be somewhat resilient in the face of this invasion. The area known now as the Sutherland Shire and the Royal National Park, for decades remained a stronghold for the Dharawal.[17] Those of the Cobbitty Barta clan who lived along the Georges River and into the Campbelltown areas were more directly exposed to the violence, disease and cultural destruction brought by the colonists. However, young leaders such as Bundel and Gogy worked with the British which led to rewards and survival for them and some of their kinspeople.[18]

Dharawal clans, such as the Wadi Wadi, who lived in what is now called the Illawarra region, were subjected to incursions of cedar-getters from the early 1800s, and then from 1815 wealthy land-holders such as Charles Throsby, George Johnston and Richard Brooks received land grants in the area. Although some Dharawal were killed in the violence that occurred with this taking of land, the Aboriginal people of the Illawarra were regarded as "friendly" and people such as the Timbery family and Toodwik were regarded favourably by the colonists.[19]

Further south, in the Shoalhaven region, early cedar-getters were driven away by the clans there and the colonists hence regarded the resident people as ferocious. However, when Alexander Berry arrived in the early 1820s to lay claim to his massive Coolangatta Estate land grant along the Shoalhaven River, he was able to negotiate a peaceful takeover through Dharawal intermediaries. The Aboriginal people of the Shoalhaven area became important workers for Berry, while they in return were able live on country with access to European goods.[20]

Due to their good positioning in terms of survival and their close cultural and geographic ties to the British economic hub of Sydney, a significant proportion of Dharawal people were able to integrate into the colonial world. By the 1830s, the coastal Dharug (Eora) people of Sydney had been decimated by colonisation and the few Aboriginal people seen in Sydney were by this stage mostly Dharawal. Dharawal people like William Worrall were regularly observed in the colonial capital and regarded as locals.[21] Furthermore, other Dharawal men such as Warroba and Johnny Crook were employed by the colonists as negotiators and trackers in places such as Van Diemen's Land, Western Australia and Port Phillip. These Dharawal men played a significant role in the founding of Melbourne and the negotiation of Batman's Treaty.[22]

Confinement to camps and reserves

[edit]By the late 1800s, the value of Dharawal people to the expanding local white society became negligible and most of the surviving members of the various clans were either left to fend for themselves in "blacks' camps" as fringe dwellers, or were pushed onto small reserves.[8]

The few surviving people around Botany Bay and along the Georges River appear to have ended up on reserves at La Perouse and at Picton, while those who lived in the Illawarra region had camps at Minnamurra, Port Kembla, Bombo, Kiama, Werri Beach and at Gerroa. A larger Aboriginal reserve was gazetted at Windang near the mouth of Lake Illawarra in the 1880s on the site of what is now the Windang Beach Tourist Park.[23][24][25][26]

Around the Shoalhaven region, most of the Dharawal people there were confined to a purpose built village on the Coolangatta Estate under the patronage of the Berry and Hay families. However, in 1901 these people were forcibly relocated onto a government reserve at Roseby Park.[27]

By the 1920s, most of these camps and reserves had been shut down and the remaining people were consolidated by the Aboriginal Protection Board into the La Perouse and Roseby Park establishments.

Dharawal identity in the present era

[edit]The descendants of the surviving Dharawal who were confined to the establishments at La Perouse and Roseby Park (Orient Point) have managed to maintain a strong Aboriginal identity despite hundreds of years of destructive colonial attitudes and policies. Those at La Perouse are consolidating their heritage through language revitalisation and re-acquiring important artefacts, while the Roseby Park people have reasserted their identity as the Jerrinja people.[28]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Dousset 2005.

- ^ a b AIATSIS 2012.

- ^ Organ & Speechley 1997, p. 7.

- ^ a b Tindale 1974, p. 198.

- ^ a b c d Attenbrow, Val (2010). Sydney's Aboriginal Past: Investigating the archaeological and historical records. Sydney: UNSW Press. ISBN 9781742231167.

- ^ a b Russell, William (1914). My Recollections. Camden: Camden News Office.

- ^ ILUA Agreement 2011.

- ^ a b c Laidlaw, Helen (2024). On Wadi Wadi Country - From the Mountains to the Sea. Sydney: Austin Macauley. ISBN 9781398495524.

- ^ Berry, Alexander (1912), Reminiscences of Alexander Berry, Sydney: Angus & Robertson, nla.obj-40716506, retrieved 14 July 2025 – via Trove

- ^ a b "The Jerrinja tribe and the Shoalhaven". New Bush Telegraph. 24 January 2019. Retrieved 14 July 2025.

- ^ Bursill 2007, p. 12.

- ^ Goodall & Cadzow 2009, pp. 88–89.

- ^ Watt 2014, p. 104.

- ^ Goodall & Cadzow 2009, p. 97.

- ^ Higgins & Collard 2020.

- ^ a b Cook, James (1893). CAPTAIN COOK'S JOURNAL DURING HIS FIRST VOYAGE ROUND THE WORLD MADE IN H.M. BARK "ENDEAVOUR" 1768-71. London: Elliot Stock.

- ^ "ABORIGINAL NAMES". The Sydney Morning Herald. No. 16, 287. New South Wales, Australia. 6 June 1890. p. 5. Retrieved 23 August 2025 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Turbet, Peter (2011). The First Frontier. Dural: Rosenberg. ISBN 9781921719073.

- ^ McCaffrey, Frank (1922). The History of the Illawarra and its Pioneers (PDF). Sydney: John Sands.

- ^ Alexander, Berry (1912). Reminiscences of Alexander Berry, with portrait and illustrations. Angus & Robertson.

- ^ Irish, Paul (2017). Hidden in Plain View. Sydney: NewSouth. ISBN 9781742235110.

- ^ Daniels, John (2022). "New South Wales Indigenous Men in Port Phillip" (PDF). Victorian Historical Journal. 93 (297): 175–192. Retrieved 26 July 2025.

- ^ "Reminiscences of Old Kiama". The Kiama Independent, And Shoalhaven Advertiser. New South Wales, Australia. 5 March 1938. p. 2. Retrieved 24 August 2025 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "CARING FOR THE BLACKS". The Daily Telegraph. No. 9676. New South Wales, Australia. 2 June 1910. p. 9. Retrieved 24 August 2025 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Aboriginal Reserve". Discover Shellharbour. Shellharbour City Museum. Retrieved 24 August 2025.

- ^ "Our Aborigines". Illawarra Mercury. Vol. XLVI, no. 45. New South Wales, Australia. 23 March 1901. p. 2. Retrieved 24 August 2025 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Removal of Aborigines' Camp". The Shoalhaven News And South Coast Districts Advertiser. Vol. 35, no. 1831. New South Wales, Australia. 20 April 1901. p. 2. Retrieved 24 August 2025 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Return of the Gweagal Spears to the La Perouse Aboriginal Community". aiatsis.gov.au. AIATSIS. 18 October 2024. Retrieved 24 August 2025.

Sources

[edit]- Bursill, L. (2007). Dharawal : the story of the Dharawal-speaking people of Southern Sydney. Sydney: Kurranulla Aboriginal Corporation.

- "Cubbitch Barta Clan of the Dharawal People Indigenous Land Use Agreement (ILUA)". Agreements, Treaties and Negotiated Settlements (ATNS) project. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- Dousset, Laurent (2005). "Tharawal". AusAnthrop (Australian Aboriginal tribal database). Archived from the original on 16 October 2014. Retrieved 4 January 2013.

- Goodall, Heather; Cadzow, Allison (2009). Rivers and Resilience: Aboriginal People on Sydney's Georges River. University of New South Wales Press. ISBN 978-1-921-41074-1.

- Goodall, Heather; Cadzow, Allison (2014). "Gogi". Dictionary of Sydney. Dictionary of Sydney Trust. Retrieved 9 October 2015.

- Higgins, Isabella; Collard, Sarah (28 April 2020). "Captain James Cook's landing and the Indigenous first words contested by Aboriginal leaders". Dictionary of Sydney. ABC News.

- "Language information: Dharawal". AIATSIS. 23 August 2012. Retrieved 4 January 2013.

- Organ, Michael K.; Speechley, Carol (1997). "Illawarra Aborigines – an Introductory History". In Hagan, J. S.; Wells, A. (eds.). A History of Wollongong. University of Wollongong Press. pp. 7–22.

- Ridley, William (1875). Kámilarói, and other Australian languages (PDF). Sydney: T. Richards, government printer – via Internet Archive.

- Tindale, Norman Barnett (1974). "Tharawal(NSW)". Aboriginal Tribes of Australia: Their Terrain, Environmental Controls, Distribution, Limits, and Proper Names. Australian National University Press. ISBN 978-0-708-10741-6.

- Watt, Bruce (2014). The Shire: A journey through time. Cronulla, Australia: Bruce Watt. pp. 11, 26, 27, 67. ISBN 978-064692019-1.

- Watt, Bruce (2019). Dharawal: the first contact people; 250 years of black and white relations. Cronulla, Australia: Bruce Watt. pp. vi, vii, 3, 5, 21, 43, 46, 50, 56, 87, 95, 111–114, 112, 121–122. ISBN 978-064699683-7.

- Williams, Shayne T. "An indigenous Australian perspective on Cook's arrival". BBC News.

Further reading

[edit]- "Bibliography of Tharawal people and language resources" (PDF). AIATSIS. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 April 2020.

- Bodkin, Frances; Bodkin-Andrews, Gawaian. "D'harawal dreaming stories". D'harawal dreaming stories.

- "Catalogue of Australian Aboriginal Tribes". Tindale's, South Australian Museum. Archived from the original on 25 September 2013.

- Kohen, J. L (1993). The Darug and their neighbours: the traditional Aboriginal owners of the Sydney region. Darug Link in association with the Blacktown and District Historical Society. ISBN 978-0-646-13619-6. (Trove and Worldcat entries)